Owen Hatherley is a firebrand leftist critic of architecture and urban space. He is the author of

Militant Modernism, an exhumation of urban utopias,

A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, on obsolete Blairite blob architecture, and

Uncommon, on Pulp (the band). Owen writes regularly for the Guardian, New Statesman, Building Design and Socialist Worker, amongst others. He runs or contributes to numerous blogs, including:

Sit down man, you're a bloody tragedy and

Kino Fist.

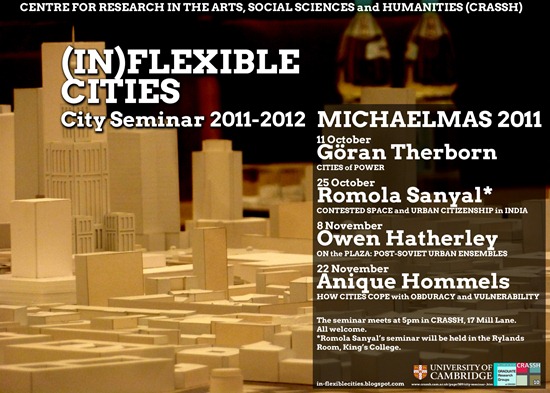

ON THE PLAZA: POST-SOVIET URBAN ENSEMBLES

Among the many things that are anathema in contemporary urban planning, one of the most demonised is the large, ceremonial public square. The vast, proverbially windswept plazas built under 'really existing socialism' from the 1920s to 1980s are widely considered to be huge and useless spaces, designed to intimidate or at least impress, lacking the intimacy and bustle of the Italian-derived Piazza.

They are often considered a Soviet innovation, though their roots are in no way socialistic, but derive from Prussian and Tsarist absolutist planning, quasi-parade grounds usually connected to wide, multi-lane boulevards – the connection of the Palace Square to Nevsky Prospekt in St Petersburg is the prototype. Yet, if these places are only of use to those in power, why is it they have been used so often – and so often successfully – in protest? From Petrograd in 1917 to the Alexanderplatz protests of 1989, through the use of the Independence Square in Kiev in the 'Orange Revolution' to the Revolution centred on Cairo's partly Soviet-planned Tahrir Square, these spaces have become focuses for mass protest – have been useful against power, in other words.

In this paper we will explore this seemingly authoritarian form of urbanism. Though focusing on the architectural spaces of these squares, it will be argued that paradoxically, these centres of power are more conducive to revolt than the new, ostensibly democratic spaces.